Introduction

This map shows the paths of Livingstone and Stanley through Africa. The stories at each marker are summarized from Martin Dugard’s

Into Africa.

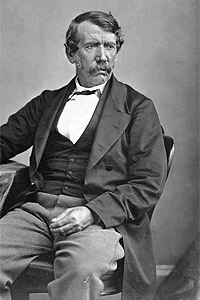

Zanzibar. April 1, 1866

Dr. David Livingstone, a renowned African explorer, devout anti-slavery crusader, and paragone of British Victorian virtue

prepares for his third and final major trek into Africa. His mission is to find the source of the Nile. Since 460 BC when

the ancient Greek Herodotus, “the father of history”, failed to discover it after traveling 600 miles inland from Cairo,

the source has remained an elusive mystery.

Recent discoveries by Livingstone’s fellow British explorers nearly prove the source is Lake Victoria. However, Livingstone

believes the source lies much farther south and that Lake Victoria and Tanganyika are part of a chain of rivers and lakes that

form the Nile. After his disastrous 1858 Zambezi expedition, Livingstone seeks to redeem himself by settling the ancient question

once and for all. And so, once more, he goes Into Africa.

Lake Nyassa. June 19, 1866

Exploring Lake Nyassa is the first vital step in proving that the lakes and rivers are, in fact, part of the Nile. He just needs

to find the connection. While exploring, he encounters the Arab slave traders that he despises. They tell him an African tribe,

the Mazitu, are ambushing all travelers and hacking them to pieces. Undaunted, Livingstone continues his search.

Casembe. November 21, 1867

Battling a fever and unable to continue on alone, Livingstone joins a caravan of Arab slave traders. Now convinced the Lualaba is the

link between the lakes and thus the the source of the Nile, Livingstone plans to travel with the slavers to Ujiji where he can resupply

and continue his search without the hated slavers.

Ujiji. March 14, 1869

After battling disease and utter despair, a broken and emaciated Livingstone reaches Ujiji. His spirits rise as he walks into the Arab

trading post but they are soon shattered when learns that almost nothing remains of his stores. They have been plundered. All of his medicine,

food, mail, and clothing, vital for trading with natives, are gone. Once again, he must rely on the slavers to survive.

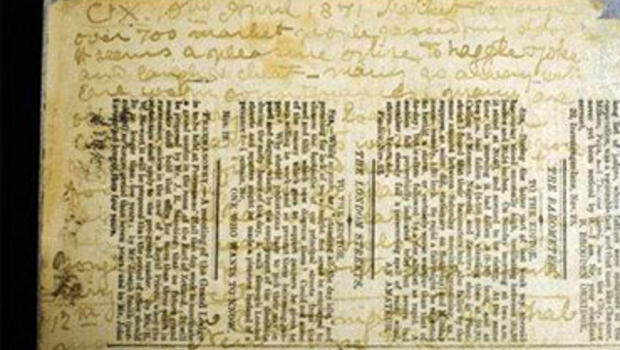

Bambarre. October 1, 1869

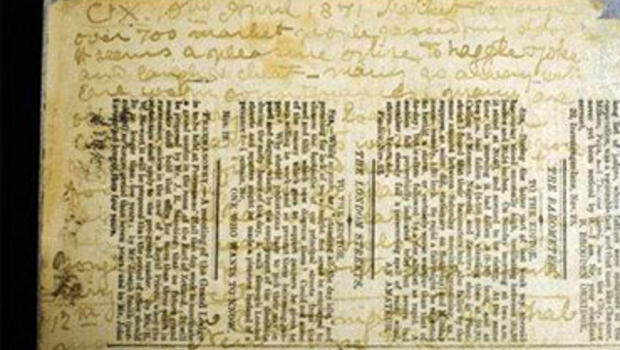

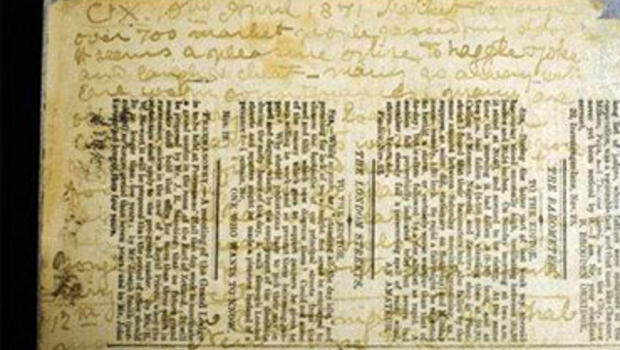

After the slave traders leave him to acquire more of their evil commodities, Livingstone lives among the tribes of Bambarre. Here he writes

the now famous Letter from Bombarre using ink made from berries and writing on pages from his copy of

The Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society.

The letter was impossible to read until 2010 when a group of academic researchers used different wavelengths of light to filter out

Livingstone’s handwriting from the printed text of the Royal Geographical Society in a process called

multispectral imaging.

In the letter, Livingstone vents his disgust for the Arab slave traders and affirms his determination to find the source of the Nile.

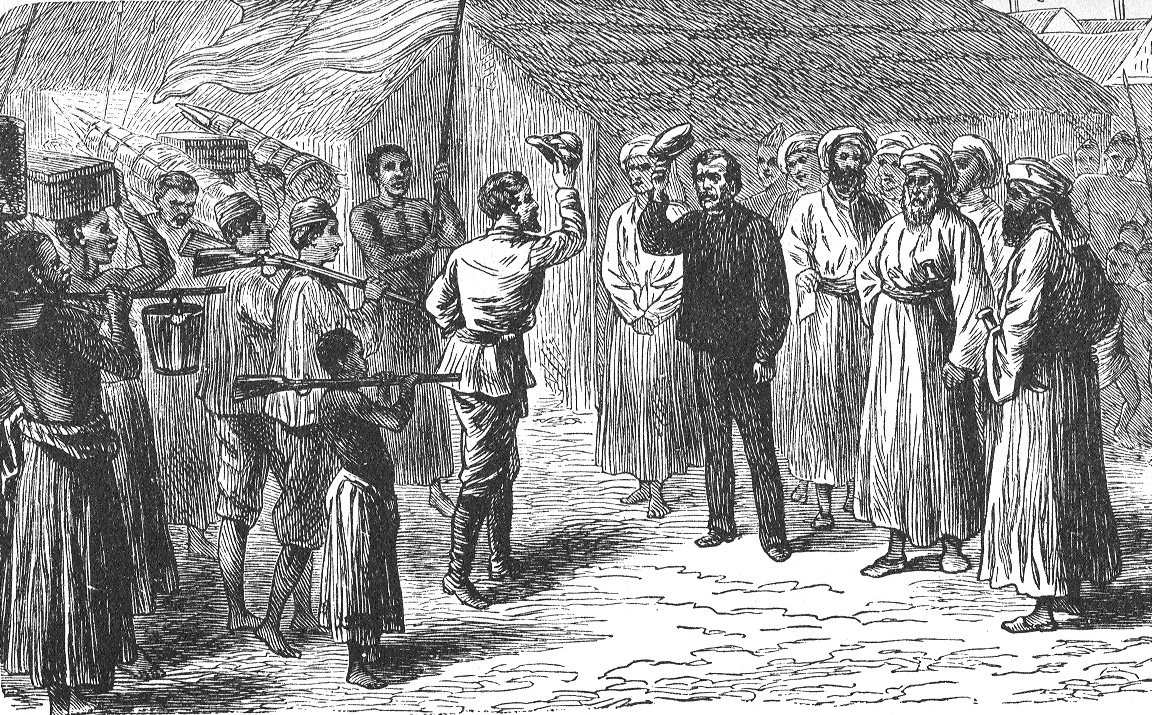

Nyangwe. July 15, 1871

Unable to afford a canoe to explore the Lualaba River, Livingstone agrees to a trade with one of the slavers. He sacrifices the supplies

he believes are waiting for him at Ujiji for a caravan to help him continue his search for the source. But days before the caravan

leaves, Livingstone witnesses an Arab massacre of the local Africans all over the price of a chicken. As Livingstone wrote in his diary:

“Shot after shot continued to be fired on the helpless and perishing. Some of the long line of heads disappeared quietly, whilst other

poor creatures threw their arms high, as if appealing to the great Father above, and sank.”

Desperately trying to stop the mass shooting, Livingstone sends one his men forward with his Union Jack, hoping the British flag might

end the slaughter. Apparently reminded of the British explorer’s presence, the Arabs cease firing. Livingstone, who had relied on the Arabs

for five years in trying to find the source, disgusted with them and himself, gives up the search and returns to Ujiji. His account

of the massacre will later spur the British public and government to demand the end of slave trade.

Ujiji. October 8, 1871

A near-skeletal Livingstone enters Ujiji to find that his stores have again been raided. A destitute and broken man, Livingstone can do nothing

except wait and hope. As he wrote “I felt, in my destitution, as I were the man who went down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell among thieves.

But I could not hope for a priest, Levite, or good Samaritan to come by on either side.” Unbeknownst to Livingstone, his good Samaritan was

closing in on Ujiji.

Zanzibar. January 6, 1871

903 Miles to Livingstone

Henry Morton Stanley, a reformed degenerate journalist for the New York Herald sets out to find Dr David Livingstone,

five years after he disappeared into the African continent. Joining him are his African guide, the former slave Sidi Mubarak

Bombay, and a former British sailor, William Shaw, along with Porters carrying hundreds of pounds of supplies. With a nearly

impossible task, he nervously begins his journey Into Africa.

The Rubeho Mountains. May 1, 1871

670 Miles to Livingstone

Stanley drives his men into the continent with the crack of his whip, “Glorying in his ability to inflict pain”. Bombay and Shaw

take the bulk of his punishment and a mutinous spirit grows in the group. One night, in the Rubeho Mountains, an ill Shaw fires a

bullet into Stanley’s tent. In this first test of his leadership, Stanley responds by cooly advising him “not to fire into my tent.

I might get hurt, you know.” His firm and calm response ends the potential rebellion. More than 100 days in, Africa is taking its

toll on the travelers, but there’s new reason to hope. Stanley hears a rumor from an Arab caravan; Livingstone is alive and on his

way to Ujiji.

Ugogo. June 1, 1871

500 Miles to Livingstone

In Ugogo, Stanley must pass through lands dominated by the Wagogo, a people even the ruthless Arab slave traders fear. As Malaria racks

his body, Stanley must be carried through the boiling-hot jungles. Four different Sultans each demand tributes of doti. Crowds of Wagogo

mock his illness and white skin. Eventually, he snaps. As a local warrior taunts him, Stanley grabs the local by the throat and beats him

in front of throngs of Wagogo. The crowd closes in on him but he beats them back with his whip. Seeing the violence in his eyes, they let

him escape.

Tabora. June 23, 1871

480 Miles to Livingstone

In Tabora, Stanley travels into the recesses of his mind as the dementia from a potentially fatal case of cerebral malaria grips him.

After two weeks of journeying through his subconscious, he awakes to find that he and his team must fight alongside the Arabs slave

traders against Mirambo, an warlord nicknamed “the African Bonaparte”. Mirambo easily defeats the Arab coalition but Stanley escapes

with his men back to Tabora. Having tried to fight his way through Mirambo, Stanley will attempt the dangerous southern trail through

thick woods. After seven weeks in Tabora, just before Mirambo attacks the city, Stanley’s group leaves for the southern trail.

Southern Trail. October 4, 1871

190 Miles to Livingstone

Without the energy to continue, a sick and, as it would turn out dying, Shaw says his goodbyes to Stanley, and turns back for Zanzibar.

Stanley continues . he faces another revolt from his men. Staring down the barrel of a porter’s gun, Stanley orders them all to continue

marching. The man lowers his gun, and they march.

Isinga. November 3, 1871

80 Miles to Livingstone

Stanley receives word from a caravan that there is a white man staying in Ujiji, just 80 miles away. Sure that the white man is Dr. Livingstone,

he presses his men forward. But they are shortly stopped by another African tribe demanding tribute. Running short of supplies, Stanley cannot

afford to pay. Instead, in the middle of the dark African night, he and his men take a dangerous back road out of town. After a 24 hour march,

they circumvent the tribe and find themselves just 46 miles from Ujiji.

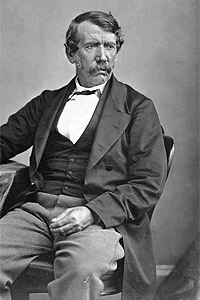

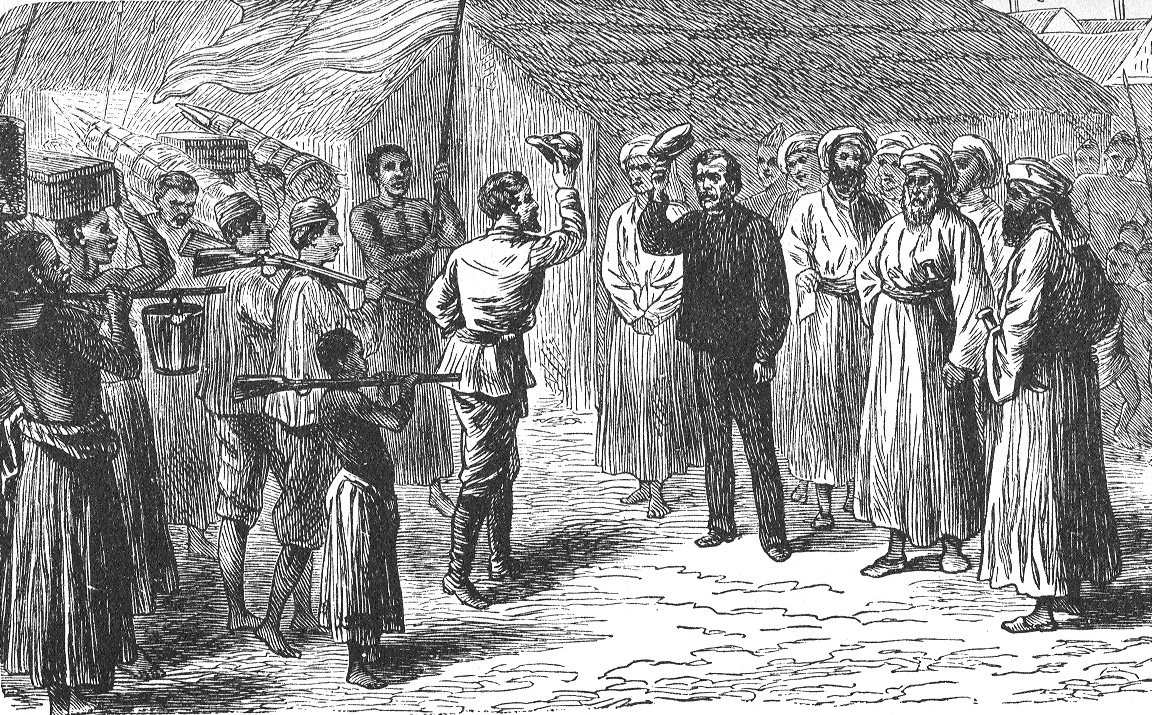

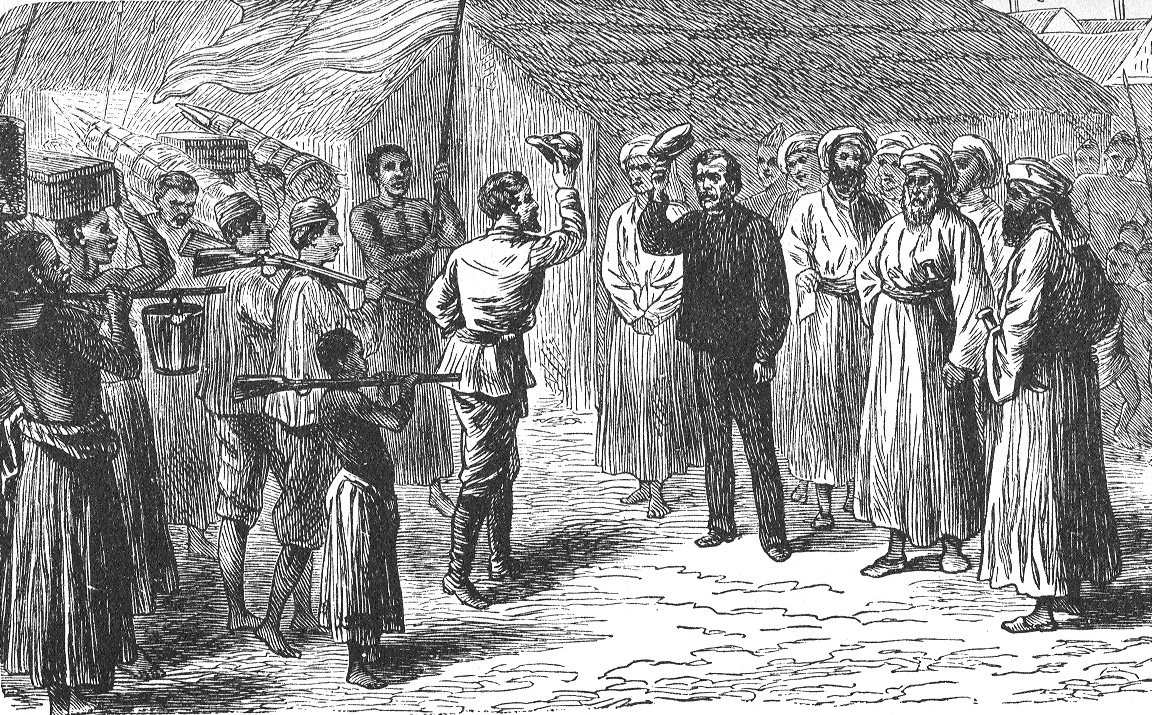

Ujiji. November 10, 1871

0 Miles to Livingstone

After 236 of longest days, traveling 975 of the hardest miles a man can endure, Henry Morton Stanley finds Dr. David Livingstone, destitute and

nearly dead, in Ujiji. Upon meeting, Stanley, in awe of his esteemed fellow traveler and surrounded by Arabs and African citizens of Ujiji, simply

asks, “Dr. Livingstone I presume?”

Over the next few weeks, Stanley basks in the Doctor’s Grace,writing in his journal that the gentle Livingstone is “not an angel, but he approaches

to that being as near as the nature of a living man will allow.” Stanley tries to convince Livingstone to leave Africa, but Livingstone refuses

and the men part after several weeks. Livingstone continues on his quest for the source of the Nile but dies on May 1st, 1873 in African village

almost 600 miles south of the source. Stanley returns to Zanzibar and becomes a world famous African explorer. Tragically, he

never learns the Grace and kindness of the older man he so idolized. Stanley went on to become a hatchet man, enforcing the brutal Belgian Congo

regime for the genocidal King Leopold II.

Introduction

This map shows the paths of Livingstone and Stanley through Africa. The stories at each marker are summarized from Martin Dugard’s

Into Africa.

Zanzibar. April 1, 1866

Dr. David Livingstone, a renowned African explorer, devout anti-slavery crusader, and paragone of British Victorian virtue

prepares for his third and final major trek into Africa. His mission is to find the source of the Nile. Since 460 BC when

the ancient Greek Herodotus, “the father of history”, failed to discover it after traveling 600 miles inland from Cairo,

the source has remained an elusive mystery.

Recent discoveries by Livingstone’s fellow British explorers nearly prove the source is Lake Victoria. However, Livingstone

believes the source lies much farther south and that Lake Victoria and Tanganyika are part of a chain of rivers and lakes that

form the Nile. After his disastrous 1858 Zambezi expedition, Livingstone seeks to redeem himself by settling the ancient question

once and for all. And so, once more, he goes Into Africa.

Lake Nyassa. June 19, 1866

Exploring Lake Nyassa is the first vital step in proving that the lakes and rivers are, in fact, part of the Nile. He just needs

to find the connection. While exploring, he encounters the Arab slave traders that he despises. They tell him an African tribe,

the Mazitu, are ambushing all travelers and hacking them to pieces. Undaunted, Livingstone continues his search.

Casembe. November 21, 1867

Battling a fever and unable to continue on alone, Livingstone joins a caravan of Arab slave traders. Now convinced the Lualaba is the

link between the lakes and thus the the source of the Nile, Livingstone plans to travel with the slavers to Ujiji where he can resupply

and continue his search without the hated slavers.

Ujiji. March 14, 1869

After battling disease and utter despair, a broken and emaciated Livingstone reaches Ujiji. His spirits rise as he walks into the Arab

trading post but they are soon shattered when learns that almost nothing remains of his stores. They have been plundered. All of his medicine,

food, mail, and clothing, vital for trading with natives, are gone. Once again, he must rely on the slavers to survive.

Bambarre. October 1, 1869

After the slave traders leave him to acquire more of their evil commodities, Livingstone lives among the tribes of Bambarre. Here he writes

the now famous Letter from Bombarre using ink made from berries and writing on pages from his copy of

The Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society.

The letter was impossible to read until 2010 when a group of academic researchers used different wavelengths of light to filter out

Livingstone’s handwriting from the printed text of the Royal Geographical Society in a process called

multispectral imaging.

In the letter, Livingstone vents his disgust for the Arab slave traders and affirms his determination to find the source of the Nile.

Nyangwe. July 15, 1871

Unable to afford a canoe to explore the Lualaba River, Livingstone agrees to a trade with one of the slavers. He sacrifices the supplies

he believes are waiting for him at Ujiji for a caravan to help him continue his search for the source. But days before the caravan

leaves, Livingstone witnesses an Arab massacre of the local Africans all over the price of a chicken. As Livingstone wrote in his diary:

“Shot after shot continued to be fired on the helpless and perishing. Some of the long line of heads disappeared quietly, whilst other

poor creatures threw their arms high, as if appealing to the great Father above, and sank.”

Desperately trying to stop the mass shooting, Livingstone sends one his men forward with his Union Jack, hoping the British flag might

end the slaughter. Apparently reminded of the British explorer’s presence, the Arabs cease firing. Livingstone, who had relied on the Arabs

for five years in trying to find the source, disgusted with them and himself, gives up the search and returns to Ujiji. His account

of the massacre will later spur the British public and government to demand the end of slave trade.

Ujiji. October 8, 1871

A near-skeletal Livingstone enters Ujiji to find that his stores have again been raided. A destitute and broken man, Livingstone can do nothing

except wait and hope. As he wrote “I felt, in my destitution, as I were the man who went down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell among thieves.

But I could not hope for a priest, Levite, or good Samaritan to come by on either side.” Unbeknownst to Livingstone, his good Samaritan was

closing in on Ujiji.

Zanzibar. January 6, 1871

903 Miles to Livingstone

Henry Morton Stanley, a reformed degenerate journalist for the New York Herald sets out to find Dr David Livingstone,

five years after he disappeared into the African continent. Joining him are his African guide, the former slave Sidi Mubarak

Bombay, and a former British sailor, William Shaw, along with Porters carrying hundreds of pounds of supplies. With a nearly

impossible task, he nervously begins his journey Into Africa.

The Rubeho Mountains. May 1, 1871

670 Miles to Livingstone

Stanley drives his men into the continent with the crack of his whip, “Glorying in his ability to inflict pain”. Bombay and Shaw

take the bulk of his punishment and a mutinous spirit grows in the group. One night, in the Rubeho Mountains, an ill Shaw fires a

bullet into Stanley’s tent. In this first test of his leadership, Stanley responds by cooly advising him “not to fire into my tent.

I might get hurt, you know.” His firm and calm response ends the potential rebellion. More than 100 days in, Africa is taking its

toll on the travelers, but there’s new reason to hope. Stanley hears a rumor from an Arab caravan; Livingstone is alive and on his

way to Ujiji.

Ugogo. June 1, 1871

500 Miles to Livingstone

In Ugogo, Stanley must pass through lands dominated by the Wagogo, a people even the ruthless Arab slave traders fear. As Malaria racks

his body, Stanley must be carried through the boiling-hot jungles. Four different Sultans each demand tributes of doti. Crowds of Wagogo

mock his illness and white skin. Eventually, he snaps. As a local warrior taunts him, Stanley grabs the local by the throat and beats him

in front of throngs of Wagogo. The crowd closes in on him but he beats them back with his whip. Seeing the violence in his eyes, they let

him escape.

Tabora. June 23, 1871

480 Miles to Livingstone

In Tabora, Stanley travels into the recesses of his mind as the dementia from a potentially fatal case of cerebral malaria grips him.

After two weeks of journeying through his subconscious, he awakes to find that he and his team must fight alongside the Arabs slave

traders against Mirambo, an warlord nicknamed “the African Bonaparte”. Mirambo easily defeats the Arab coalition but Stanley escapes

with his men back to Tabora. Having tried to fight his way through Mirambo, Stanley will attempt the dangerous southern trail through

thick woods. After seven weeks in Tabora, just before Mirambo attacks the city, Stanley’s group leaves for the southern trail.

Southern Trail. October 4, 1871

190 Miles to Livingstone

Without the energy to continue, a sick and, as it would turn out dying, Shaw says his goodbyes to Stanley, and turns back for Zanzibar.

Stanley continues . he faces another revolt from his men. Staring down the barrel of a porter’s gun, Stanley orders them all to continue

marching. The man lowers his gun, and they march.

Isinga. November 3, 1871

80 Miles to Livingstone

Stanley receives word from a caravan that there is a white man staying in Ujiji, just 80 miles away. Sure that the white man is Dr. Livingstone,

he presses his men forward. But they are shortly stopped by another African tribe demanding tribute. Running short of supplies, Stanley cannot

afford to pay. Instead, in the middle of the dark African night, he and his men take a dangerous back road out of town. After a 24 hour march,

they circumvent the tribe and find themselves just 46 miles from Ujiji.

Ujiji. November 10, 1871

0 Miles to Livingstone

After 236 of longest days, traveling 975 of the hardest miles a man can endure, Henry Morton Stanley finds Dr. David Livingstone, destitute and

nearly dead, in Ujiji. Upon meeting, Stanley, in awe of his esteemed fellow traveler and surrounded by Arabs and African citizens of Ujiji, simply

asks, “Dr. Livingstone I presume?”

Over the next few weeks, Stanley basks in the Doctor’s Grace,writing in his journal that the gentle Livingstone is “not an angel, but he approaches

to that being as near as the nature of a living man will allow.” Stanley tries to convince Livingstone to leave Africa, but Livingstone refuses

and the men part after several weeks. Livingstone continues on his quest for the source of the Nile but dies on May 1st, 1873 in African village

almost 600 miles south of the source. Stanley returns to Zanzibar and becomes a world famous African explorer. Tragically, he

never learns the Grace and kindness of the older man he so idolized. Stanley went on to become a hatchet man, enforcing the brutal Belgian Congo

regime for the genocidal King Leopold II.