How to Create New Knowledge

Contents

For thousands of years, our ancestors lived in a world lit only by fire, generation after generation dying from the same diseases, wars, and famines that killed their ancestors.

Every so often, they would stumble upon an occasional improvement that would make their lives ever so slightly more tolerable. But so rare and random were these meager improvements that they appeared as nothing more than the occasional gift from the gods, like Prometheus gifting us fire.

But then we became the masters of our own fate.

Sometime around the 16th century, we began to question the world around us, and, after thousands of years of mere survival, we began to make progress. Not just in a single area like farming or war but in almost all directions and almost simultaneously.

Because this time, we stumbled on the answer to the most important question - how to create new knowledge. That discovery precipitated The Enlightenment - that we’re still living in today.

Popper’s Theory of Knowledge Creation

The growth of knowledge since the 16th century is the subject of the philosopher and epistemologist Karl Popper’s work. I will review, summarize, and expand on his work in a series of evolving essays.

We’ll begin with Popper’s explanation of how we create new knowledge. While humans discovered the system of knowledge creation in the 16th century, until Popper’s work on the Logic of Scientific Discovery in the mid 20th century, nobody had developed a precise explanation of how the system of knowledge creation worked.

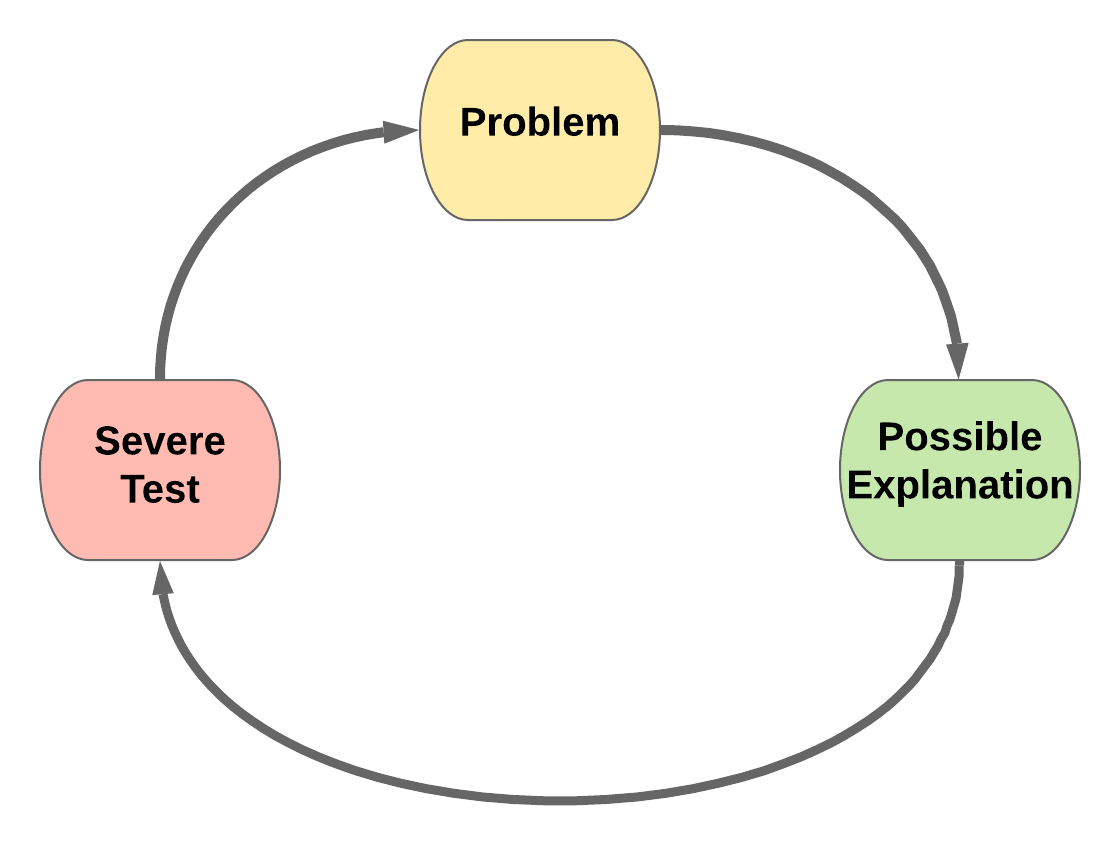

Popper’s theory is strikingly simple.

We start with a problem, we create an explanation that might solve the problem, and we then subject that explanation to severe tests to try to disprove it.

For example, let’s start with a problem.

Why do some objects fall faster than others?

Problems like this are a gap in our understanding. A question we can’t answer.

Next, we create an explanation that could potentially solve the problem.

Some objects fall faster than others because they are heavier.

It doesn’t matter where these explanations come from. In our example, we might think “heavier objects are harder to lift, and therefore they fall faster”.

Then we subject our explanation to a severe test, one that could disprove the explanation.

We’ll drop a rock and a feather off our roof and see which one hits the ground first.

The test must have the potential to disprove our explanation. In our case, if the feather hits the ground first, we can determine that heavier objects do NOT fall faster.

Of course, in our example, the feather does not hit the ground first and thus does NOT disprove our explanation.

We might be tempted to say that we’ve proven our theory, the heavier object did indeed fall faster. But that’s not what the test does.

We can never definitely prove our explanation, we can only subject it to more and more severe tests until its “proved its mettle”.

That’s a critical result of Popper’s epistemology, all knowledge is provisional. The best we can do find errors in our thinking with tests and create new explanations that survive our tests without the errors of our previous explanations.

In fact, our example demonstrates exactly this. Because, as many high school physics students are shocked to discover, heavier objects do NOT fall faster than lighter ones.

Had we subjected our explanation to another severe test, by say, a dropping a large flat rock and a small round pebble off the roof, we would have discovered that the pebble will hit the ground first, thus disproving our theory.

And yet from the time of Aristotle to the time of Galileo, the most highly educated people in the Western world believed that heavier objects fell faster.

I find this shocking. For thousands of years, nobody bothered to drop a pebble and rock off a roof to see if the rock fell faster?

But it demonstrates that before the Enlightenment, we didn’t know how to create new knowledge by testing our theories. We didn’t even try.

It also demonstrates another problem. Throughout the Middle Ages, Aristotle was considered the last word on what he called physics. To disagree with him was downright heretical.

At that time, the only defense of a theory of physics was an appeal to his authority, just as the only defense of moral theory (in Western Europe) was an appeal to the Bible or the church.

Appeals to authority show one possible reason why it took so long for the Enlightenment to get started. Society has to be structured to accept criticism of explanations, and people have to agree to subject their ideas to severe tests and throw them out when they don’t survive those tests.

Popper calls such a society an Open Society, one that’s open to change and criticism.

Conclusion

The actual reason why some objects fall faster than others (at least near the surface of the Earth) is that some objects are more aerodynamic than others.

But to explain aerodynamics, we need to understand many complex phenomena, like wind resistance, friction, chemistry, and gravity. In fact, I’d venture that a society that has generated enough knowledge to adequately explain why some objects fall faster than others has generated enough knowledge to put a man on the moon.

As our seemingly trivial example shows, Popper’s system of knowledge creation is generalizable. It can and does create new knowledge in all fields of human endeavor.

With it, we can learn how to describe the movement of the heavenly bodies in shockingly precise details.

We can learn how to govern ourselves without violence.

We can learn how to create unending new sources of wealth

We can even learn to tell the difference between what is morally right and morally wrong.

Socratic Owl

Socratic Owl